One of the perks of a class-free summer is the ability to go down any tempting rabbit hole without the guilt of a neglected problem set hanging over my head. I was curious about Joseph Black, the 18th century Scottish chemist known for discovering carbon dioxide and magnesium. His studies of latent and specific heat became the foundations of the field of thermodynamics. Black flourished during a time of creative and cultural growth known as the Scottish Enlightenment. From the late 1600s to the early 1800s, Scotland bubbled over with intellectual giants and produced men like Frances Hutcherson, Adam Smith, Henry Kames, and David Hume.

Sam Kean, author of Caesar’s Last Breath: Decoding the Secrets of the Air Around Us credits Black with being not only brilliant, but fun. He gave exciting public lectures where he filled balloons with light gases—audiences were sure that invisible strings were lifting the balloons to the ceiling. Black isolated carbon dioxide in 1754, when he was about 26 years old. Later he figured out that people exhale carbon dioxide after he put a beaker of slaked lime in the rafters of a Scottish church before a service. When exposed to carbon dioxide, slaked lime produces milky precipitates. At the end of the 10-hour service (!), the fluid in the beaker was white from the preacher’s exhalations as well as the other human gas-bags in the room. Here is a picture of him in his later years; I admire his luxurious eyebrows, especially the right one.

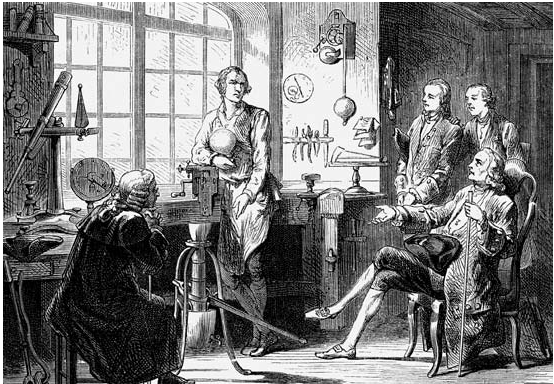

Black liked to drink and drank a lot of sherry and claret with his cronies, Adam Smith and David Hume. This did not, however, slow him down. In addition to being a chemist, he was a practicing physician and busied himself with creating industrial processes, like bleaching systems for the linen industry. In 1755, he became Professor of Medicine and Chemistry at the illustrious University of Edinburgh, a position he held for more than 30 years. Adam Smith said, “No man I know has less nonsense in his head than Doctor Black.” Black also was close friends with James Watt, an instrument maker at the University of Glasgow famous for improving the design of the steam engine that fueled the industrial revolution. Below is picture of Black visiting Watt in his workshop. I doubt it was that clean and orderly.

Voltaire said, “We look to Scotland for all our ideas of civilization.” The Scots were leading the charge to a more humanistic, modern society with their writings about civil liberties, philosophy, politics, science, and economics. I totally drank the same kool-aid as Voltaire after reading Arthur Herman’s How the Scots Invented the Modern World. Herman writes, “Basic principles that the Scottish Enlightenment enshrined: common sense, experience as our best source of knowledge, and arriving at scientific laws by testing general hypotheses through individual experiment and trial and error.” What’s not to love?

This focus on learning and education had deep roots in the culture. In 1696, the Scottish parliament’s “School Act” required every parish to have a school. By the end of the 1700s, Scotland had a literacy rate higher than any other country, and publishing houses and paper mills were a large chunk of the domestic economy. They believed that the goal of education was not only to understand the world around us, but also to spread the wealth and teach others. And they were excellent at teaching others. Only Episcopalians could attend Oxford, Cambridge, or Trinity in the 1700s, so non-Episcopalians from all over flocked to the Universities of Glasgow and Edinburgh.

Edinburgh in particular became home to the world’s leading medical school, famous for producing the most effective physicians. Interestingly, doctors-in-training at Oxford and Cambridge were discouraged from touching patients, leaving actual physical contact to servants. Professor William Cullen (Adam Smith’s personal physician) at the University of Edinburgh thought that was nonsense. He did all kinds of crazy things, like lecturing in English instead of Latin and encouraging students to challenge him in class. Cullen’s motto was “no facts, no theory” – without data, how could you have a meaningful understanding of how things work? In 1750, Cullen’s fellow professor John Rutherford created the first clinical rounds system for training young doctors.

Herman writes:

The hallmarks of Scottish medicine were close clinical observation, hands-on diagnosis, and thinking of objects such as the human body as a system–not so different from the practical approach of engineers such as James Watt. In fact, science and medicine were probably more closely linked in Scotland than any other European country. Together with mathematics, they formed the triangular base of the Scottish practical mind.

Scottish doctors lay the groundwork for both modern medical practices and the discipline of public health. Edinburgh-educated Thomas Percival persuaded Manchester hospitals to keep birth and death statistics to trace the path of epidemic diseases. He also created what is probably the first code of medical ethics. John Farrier, also Edinburgh-educated, set up the world’s first board of health in Manchester, and he was influential in spreading the practice of disinfecting fever wards in hospitals.

I wish there were some women to add to the list of Scottish chemists, philosophers, and physicians, but a desultory dig into Google revealed…not much. Prof. Charles Hope (Charles Darwin was one of his students) of the University of Edinburgh gave a short course of chemistry lectures attended by ladies in the 1826, but that’s about it.

Lately, I have pestering friends and family with tidbits of Scottish prowess. For those who have the appetite, I will close with some snack-like treats:

- Charles Maitland-performed the first smallpox inoculation in1718

- James Lind–figured out that scurvy could be cured by citrus fruits in 1747 and did the first controlled experiment in history to test his theory

- John Pringle–a Scottish physician (and often Ben Franklin’s travel companion) developed idea that noncombatants are army medics and wounded and inspired the creation of the Red Cross

- James Hutton–first person to suggest that that the earth is older than 6,000 years. In 1788 published his theory that earth long predated man and would last long afterward. Known as the Father of Modern Geology

- William Murdoch–James Watt’s assistant, invented gas lighting in the 1790s

- James Simpson–introduced chloroform as anesthetic for surgery in 1847

- Sanford Fleming–came up with idea of worldwide standard time zones

- Lord Kelvin–proposed an absolute temperature scale in 1848 (known as the Kelvin scale). Formulated the second law of thermodynamics-heat will not flow from a colder body to a hotter body

- Livingstone–19th century missionary, explorer, philanthropist, and physician. Tried to find source of the Nile, instrumental in ending the East African Arab-Swahili slave trade

- Andrew Hallidie–Scottish engineer designed and built the San Francisco cable car network 1873

- Alexander Graham Bell–patented first telephone. Gifted teacher of the deaf (his Mom and wife were deaf), Helen Keller was his most famous pupil

That’s some serious cocktail party trivia!

LikeLike