Francis Su is a professor of mathematics at Harvey Mudd College and was the President of the Mathematical Association of America (MAA) for a couple of years. Obviously, a smart guy. I love Professor Su because he is obsessed with the eudaimonia, a Greek word that is translated a bunch of different ways, like happiness, welfare, or human flourishing. Aristotle described eudaimonia as ‘doing and living well.’

I was really taken by this article about Su published in Quanta magazine in 2017. If you’re not familiar with Quanta, I highly recommend it. It’s an on-line source of math and science research (with articles like “How Insulin Helped Create Ant Societies” and “How Does Life Come From Randomness?” I mean, what’s not to love?) For Su, mathematics hits all the primary human desires for truth, beauty, justice, play, and love. He thinks doing math can help you live your best life, whomever you are. At an MAA meeting, he mentioned Christopher, a man convicted of armed robbery who taught himself math from textbooks and who asked Su how to continue his studies.

Su actually worries about who is discouraged from pursuing math, and he worries about it because he thinks everyone should get a chance to experience the joy of the pursuit of knowledge. It doesn’t matter whether they will achieve success at the highest level, or any level really, because the pursuit itself is integral to human flourishing. When we seek truth, think rigorously, are intellectually honest, and persevere, we are living a life where we can flourish.

I like this, it gives me hope. Last year, I completed three classes and dropped an equal number for various reasons. Although at times I was frustrated and discouraged, I’m intrigued by the place where molecular biology and chemistry intersect. It’s a world that is crazily, bizarrely small. Human cells are between 1 to 100 micrometers in diameter (a micrometer is one millionth of a meter) and atoms range from 0.1 to 0.5 nanometers (a nanometer is one billionth of a meter). As we unravel tiny biochemical mysteries, we can radically change peoples’ lives. Through gene therapy and other treatments, we can slay demons that have ruined and destroyed lives through all of human history. Imagine a world where cancer and cystic fibrosis are an inconvenience and not a death sentence.

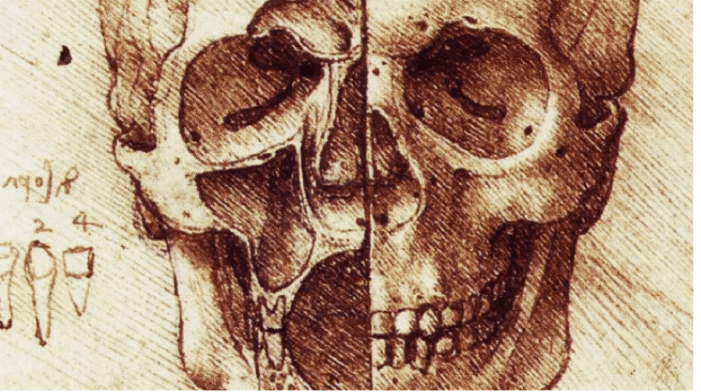

Over the summer, I read Leonardo Da Vinci by Walter Isaacson. Or more accurately, I listened to the plummy narration by Alfred Molina on Audible. I thought about eudaimonia a lot while listening to the book. If there is anyone who embodies human flourishing, it’s Leonardo, a left-handed vegetarian who liked to wear rose tunics, rarely turned in a commission on time, and never felt like a painting was ever truly done. He would immerse himself into the study of human anatomy (above is one of da Vinci’s anatomical drawings), and artistic perspective, and tweak his paintings to reflect his findings, sometimes decades after beginning the piece. He struggled with math and with Latin, subjects in which many learned men of his generation were well-versed.

Isaacson is fascinated by Leonardo’s insatiable curiosity and his ability to let his imagination not just run free, but run rampant—his notebooks contained plans for a helicopter, a self-propelled cart, and scuba gear, among other things, that were centuries before their time. The notebooks contain lots of Leonardo’s “to do” lists. Two of the most awesome entries: “Describe the tongue of woodpecker” and “Go every Saturday to the hot bath, where you will see naked men.”

For Isaacson, Leonardo is the shining example of an unusual genius who was creative and innovative across multiple disciplines. Isaacson also calls Leonardo an understandable genius because he had some serious strikes against him in the 15th century world he was born into. He didn’t have much formal schooling and was born out of wedlock. He also procrastinated a lot, was a moody perfectionist, and was a sucker for at least one young, feckless man. What Leonardo did have: intense observational skills, curiosity, a strong will, and ambition.

Isaacson is so inspired by Leonardo’s example of an incredibly rich life of creation and imagination that he poses the question, “How can we be more like Leonardo?” His answers, paraphrased from the final chapter of the book:

- Be relentlessly and randomly curious about everything around you

- Seek knowledge for its own sake—it doesn’t have to be useful, do it for pure pleasure

- Retain a childlike sense of wonder—keep asking yourself why things are the way they are, like why IS the sky blue?

- Observe acutely—let your observations fuel your curiosity

- See things unseen—use fantasy to imagine what does not exist

- Go down rabbit holes—investigate something that interests you, just for the hell of it (Isaacson calls it the “pure joy of geeking out.”)

- Respect facts—critical thinking and observational experiments are your friends

- Be fearless about changing your mind based on new information—if the results of your experiment don’t support your theory, be ready to change your mind

- Procrastinate—this one should be easy. Leonardo thought creativity required lots of time for ideas to marinate and gel

- Let the perfect be the enemy of the good —don’t settle for OK when you know you can do better (I think most of us can take a pass on this one)

- Avoid silos—a lot of good creative work is found where different disciplines intersect

- Let your reach exceed your grasp—so, you can’t understand a certain problem, but you can understand why some problems are so hard to solve

- Create for yourself, not just for patrons—we all need creative outlets to lead fulfilling lives

- Collaborate—do fun things and absorbing projects with smart people

- Make lists—the weirder, the better

- Take notes on paper—make your own notebooks of discovery

- Be open to mystery—you might solve it and learn something, or you might just marvel at something that fascinates you

In a few weeks, I’ll start taking classes again. I’m sure that I can manage the procrastination part … we’ll see about the rest.

Excellent! Thank you for summarizing LdV so I don’t have to read Isaacson’s book.

LikeLike

Words to live by.

LikeLike