A palate cleanser of art and science is in order after 11 weeks of molecular biology. It was a challenging class, with a gifted instructor and a high quality TA. I really wish I had taken it as an undergrad – I love the combination of chemistry and biology. Chemistry never lies – under the same conditions, the same reaction will always happen. Biology is messy, complicated, and alluring, because a seemingly endless combination of factors influence the outcome of biological system interactions. Untangling cause and effect becomes even more complex when feedback loops are involved.

A palate cleanser of art and science is in order after 11 weeks of molecular biology. It was a challenging class, with a gifted instructor and a high quality TA. I really wish I had taken it as an undergrad – I love the combination of chemistry and biology. Chemistry never lies – under the same conditions, the same reaction will always happen. Biology is messy, complicated, and alluring, because a seemingly endless combination of factors influence the outcome of biological system interactions. Untangling cause and effect becomes even more complex when feedback loops are involved.

I pounded my head against lots of scientific papers trying to get at the heart of the research and why it mattered. Here is the kind of material we looked at in class:

In both two- and three-dimensional culture, NPCs form kidney organoids containing epithelial nephron-like structures expressing markers of podocytes, proximal tubules, loops of Henle and distal tubules in an organized, continuous arrangement that resembles the nephron in vivo.

Translation: Hey, we can grow functioning kidney cells in a petri dish!

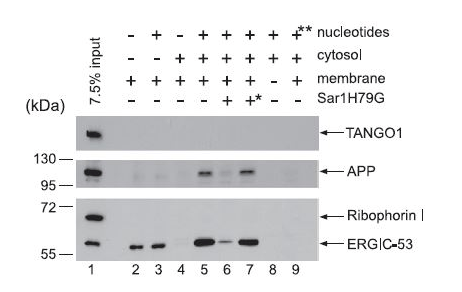

Or what became the bane of my existence, interpreting western blots, which are a way to identify specific proteins from a mixture of a bunch of different proteins:

Translation: TANGO 1 is not found in transport vesicles leaving the endoplasmic reticulum. To me it looks like a weird test result from something done on a Soviet submarine in the 1950s.

My favorite topic of the quarter involved using scorpion venom from the Israeli Death Stalker to light up brain tumors. The venom binds to cancer cells, and when you tag those venomous molecules with fluorescent markers, the cancer cells glow. Here’s what it looks like:

This glowing paint allows surgeons to resect brain tumors without taking out normal brain tissue. If heathy brain tissue is removed, neurological damage can result, and if all of the tumor bits are not resected, remaining cancerous cells can multiply and cause havoc. Dr. Jim Olsen at Fred Hutch developed the tumor painting technique. He has a tattoo of the scorpion venom’s chlorotoxin molecule on his arm and is one of my heroes. He explains the tumor paint process here. For me, the video emphasizes that behind all the exciting advances in medical research and treatments, real people are benefiting, and some modicum of suffering is diminished.

What’s intriguing about the tumor technique is that it is both powerfully effective and visually striking. A number of artists have been inspired by the beauty of the molecular world. The illustration at the beginning of this post is by David Goodsell, an associate professor at Scripps Research Institute. It’s the cross section of a single bacterial cell shown at one million times magnification and is the cover of his book, The Machinery of Life. The book is chock full of his gorgeous watercolor illustrations of cells, as well as cool computer generated images of molecules. Most molecules are colorless, so Goodsell comes up with his own lush and trippy color palettes to highlight cell interiors. He has a web page of his work and encourages people to go ahead and use them for personal presentations – he just asks that they give him credit. Check out some of his creative endeavors depicting E. coli, collagen, and cytoplasm:

Mike Tyka is a scientist/artist who makes sculptures of protein molecules. He has a Ph.D. in Biophysics, currently works at Google, and co-founded ALTSpace, a community art workshop in Seattle. I love that he helped create the Groovik’s Cube, billed as “a 35ft tall, functional, multi-player Rubik’s cube.” You can watch its time-lapse assembly here. Two of his sculptures are shown below. On the left is the Angel of Death, made out of copper and steel. It’s a representation of the ubiquitin molecule– once a protein is tagged with ubiquitin, it will be degraded and its components will be recycled by the cell. On the right is Tears, depicting a lysozyme with a carbohydrate; the carbohydrate part in is bronze, the lysozyme in clear lead glass. The lysozyme is breaking down the carbohydrate, which I assume is part of a creepy bacteria trying to invade a nice, normal cell.

Months ago I came across a few articles about setting the folding of proteins to music. Biology is all about protein folding—the physical process of proteins assuming a 3-dimensional structure. That structure is essential to their function. If a protein is misfolded, all kinds of stuff can go horribly wrong, from allergies to Alzheimer’s.

Sonification is the technique of taking data and transforming it into melodies. In other words, why not listen to data, instead of just looking at it? Three questions guide the research: what could protein folding data sound like, what are the analytical benefits, and can you hear anomalies in the data?

Well, the music doesn’t sound that good to me, but I love the idea of taking a novel approach to analyzing data. Researchers used some funky software to convert the folding shapes of three proteins to musical code. People can just listen to the sound track to identify patterns or wrong notes.

I think it would be really excellent to have Patrick and Rowan’s talented and amazing tap teacher, Josh Scribner, choreograph something to the music of protein folding. This would be appropriate given the name of his troupe is Alchemy Tap Project (ATP, you know, like adenosine triphosphate) and the annual show is called Beat Science. I imagine an audience of tap dancing scientists saying, “Wow, that interpretation of ubiquitin was quite piquant,” or “The tubulin was a bit off, no?”